History_

The Columbia River Gorge has existed as a sea-level passage through the Cascades for millions of years, and for untold thousands of years people have taken advantage of this natural highway. Their myriad stories comprise the region's human history

Spanning roughly 85 miles along the border of Oregon and Washington, the Columbia River Gorge is one of the Pacific Northwest’s most spectacular natural wonders. It is the only sea-level passage through the Cascade Mountains—a dramatic corridor where sheer cliffs, thundering waterfalls, and diverse ecosystems meet. Today, it is protected as a National Scenic Area and remains a place where communities live, cultures endure, and millions of visitors come each year for its beauty, history, and recreation.

The landscapes here are a study in contrast. In the west, mist-fed rainforests flourish with more than 75 inches of annual rainfall, while the east transitions into golden grasslands that see less than 15 inches. Elevations range from sea level at the river to nearly 4,000 feet along surrounding peaks, creating an impressive variety of ecosystems in a short distance. The Gorge’s origins date back over 40 million years with volcanic activity that shaped the Columbia Basin. Between 6 and 17 million years ago, massive lava flows formed thick basalt layers, and during the last Ice Age, cataclysmic floods from glacial Lake Missoula repeatedly scoured the canyon, carving steep walls and creating the waterfalls and unique rock formations visible today.

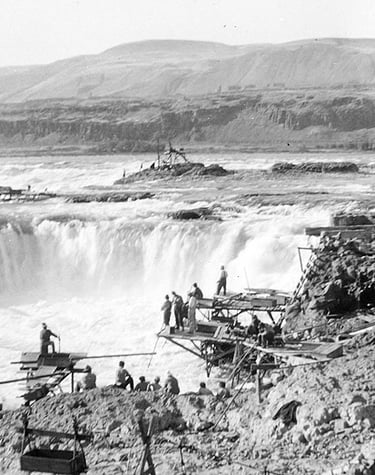

Humans have lived along the Columbia River for at least 10,000 to 13,000 years. For Indigenous peoples—including Chinookan- and Sahaptin-speaking tribes—the river was, and remains, a lifeline, providing salmon, sturgeon, lamprey, and other vital resources. Celilo Falls, once one of North America’s most important fishing and trading hubs, drew tribes from across the West to exchange goods and knowledge before it was submerged by The Dalles Dam in 1957. The river was not only a source of sustenance but also a place of deep spiritual meaning, reflected in names such as Nch’i-Wána, meaning “The Great River” in Sahaptin. Fishing rights protected by treaties continue to connect modern tribal members to their ancestral waters.

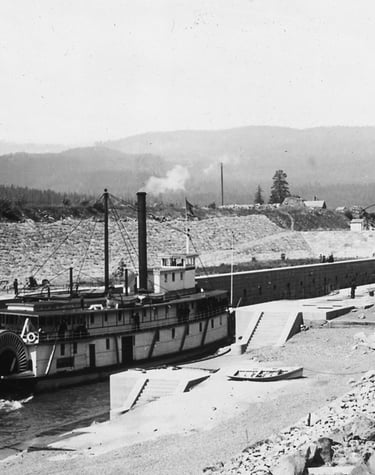

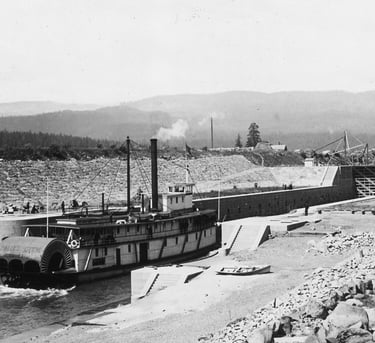

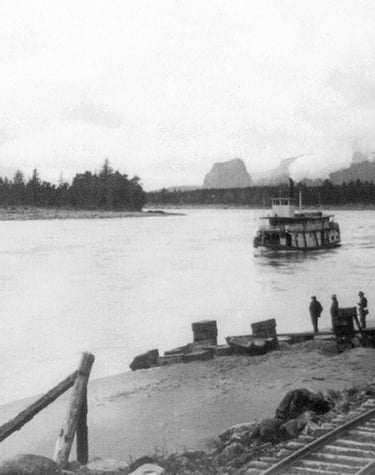

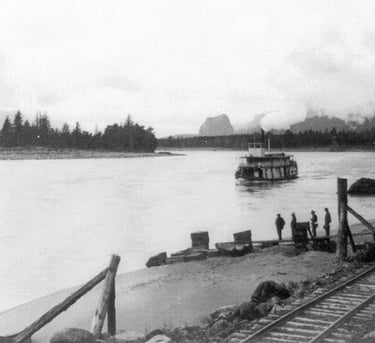

European contact began in the late 1700s when explorers like American Captain Robert Gray and British Captain George Vancouver charted parts of the river. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition navigated the Gorge on their way to the Pacific, recording its towering cliffs, diverse wildlife, and thriving Indigenous villages. Their journals tell of the hazards of swift waters and the breathtaking beauty of the canyon. By the mid-1800s, pioneers on the Oregon Trail reached The Dalles, where they had to decide whether to float their wagons down the Columbia’s rapids or take the rugged Barlow Road around Mount Hood. The arrival of steamboats and later railroads transformed the Gorge into a major transportation route for wheat, timber, and goods traveling between inland farms and coastal ports.

The 20th century brought industrial expansion, with lumber mills, fisheries, and hydroelectric dams like Bonneville in 1937 and The Dalles in 1957. While these developments improved navigation and generated electricity, they also flooded significant cultural sites and changed the river’s natural rhythms. Yet the Gorge adapted, becoming not just an industrial corridor but a world-class destination for outdoor adventure. Visitors come for the more than 90 waterfalls on the Oregon side alone, including 620-foot Multnomah Falls, one of the tallest year-round waterfalls in the United States. Over 200 miles of hiking and biking trails offer everything from gentle riverside walks to strenuous climbs with sweeping views. Steady winds make Hood River a global hub for windsurfing and kiteboarding, while calmer stretches of the Columbia and nearby rivers are perfect for kayaking and paddle boarding. The Historic Columbia River Highway provides unforgettable vistas from points like Crown Point’s Vista House, and the region’s wildlife—seasonal salmon runs, raptor migrations, and spring wildflower blooms—draws nature lovers year-round. Wineries, breweries, and farm-to-table restaurants showcase the area’s agricultural abundance.

Along the way, small towns give the Gorge its human character. Hood River is known for its orchards, outdoor sports, and lively dining scene. The Dalles blends deep historical roots with a sunny climate. Cascade Locks serves as a hub for hiking, fishing, and river travel, while Stevenson offers access to Washington-side trails and craft breweries. Each community blends tourism, agriculture, and industry, offering unique stops along any Gorge journey.

In 1986, Congress created the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area to safeguard the region’s natural beauty while supporting local economies. Today, the U.S. Forest Service, the Columbia River Gorge Commission, tribal nations, and local governments work together to balance recreation, conservation, and economic vitality. The future will bring challenges—recovering from wildfires, adapting to climate change, managing tourism to avoid overcrowding, and protecting forests, water, and wildlife corridors—but the Gorge endures as a place where history, culture, and nature converge. Standing at a windswept overlook, watching the Columbia’s steady current, it is easy to feel the pull of thousands of years of human stories and the enduring wonder of the land.

Sources & Further Reading

"The Columbia River," William Lyman, Binfords & Mort Publishers

"Oregon and the Pacific Northwest," Lancaster Pollard, Binford & Mort Publishers

"Barlow Road," Clackamas and Wasco County Historical Societies, J.Y. Hollingsworth Co.

"Nch'i-Wana, Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land," Eugene S. Hunn, University of Washington Press

"Stone Age on the Columbia River," Emory Strong, Binfords & Mort Publishers

"Handbook of North American Indians," Vol. XII, edited by Deward E. Walker Jr., Smithsonian Institution

For More Information On The History Of The Gorge, Be Sure To Visit

Bonneville Dam Visitor Center - In Oregon and Washington, 541-374-8820

Cascade Locks Historical Museum - Cascade Locks, OR, 503-374-8535

Columbia Gorge Discovery Center & Wasco County Historical Museum - The Dalles, OR, 541-296-8600

Columbia Gorge Interpretive Center - Skamania County Museum in Stevenson, WA, 509-427-8211

Fort Dalles Historical Museum - The Dalles, OR, 503-296-4547

Gorge Heritage Museum - White Salmon, WA, 509-493-3228

Hood River County Historical Museum - Hood River, OR, 541-386-4547

Hutson Museum - Parkdale, OR, 541-352-6808

Maryhill Museum of Art - Goldendale, WA, 509-773-3733

Stonehenge - 3 miles east of Maryhill Museum